Jac Berrocal + David Fenech + Vincent Epplay – Antigravity

release date : April 27 2015

label : blackest ever black

format : LP / CD

Antigravity is the first album from the trio Jac Berrocal + David Fenech + Vincent Epplay, released on the Blackest Ever Black label. Featuring Anna Byskov on vocals on one track. Mastered by the legendary Noel Summerville.

Press release from the label :

Antigravity is a trio album from legendary trumpeter Jac Berrocal and two fellow travellers in the French avant-garde, David Fenech and Vincent Epplay. A lugubrious mise-en-scène in which ice-cold outlaw jazz meets musique concrète, DIY whimsy and dubwise studio science, all watched over by the lost souls and hungry ghosts of rock ‘n roll. Born in 1946, Berrocal is the embodiment of saturnine, nicotine-stained Parisian cool, but he is also one of a kind: indeed, “trumpeter” is hardly an adequate epithet for this musician, poet and sometime film actor who came of age in the ‘70s Paris improv scene, where the boundaries between music, art and theatre were porous and begging to be breached. Inspired by bebop, chanson, free jazz, beat poetry, early rock ‘n roll and myriad Eastern influences, and with an iconoclastic, anything-goes approach to instrumentation and technique that would later align him with post-punk sensibilities, Berrocal blazed an eccentric and unstoppable trail across the underground throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s, both solo and as part of the Catalogue group he co-founded. During this time his uproarious performances routinely wound up jazz and rock audiences alike, but earned the admiration of no small number of wised-up weirdos: Steven Stapleton invited him to perform on two Nurse With Wound albums, and other notable collaborators in his career include Sunny Murray, Lizzy Mercier-Descloux, Lol Coxhill, Yvette Horner and James Chance. In the 90s his protean achievements were celebrated on the Fatal Encounters compilation, but far from slowing down in the autumn of his life, Berrocal has maintained an extraordinary work-rate, keeping studio dates with Pascal Comelade, Telectu and Jaki Liebezeit, among others. In 2014 he released his first solo album proper in 20 years, MDLV.

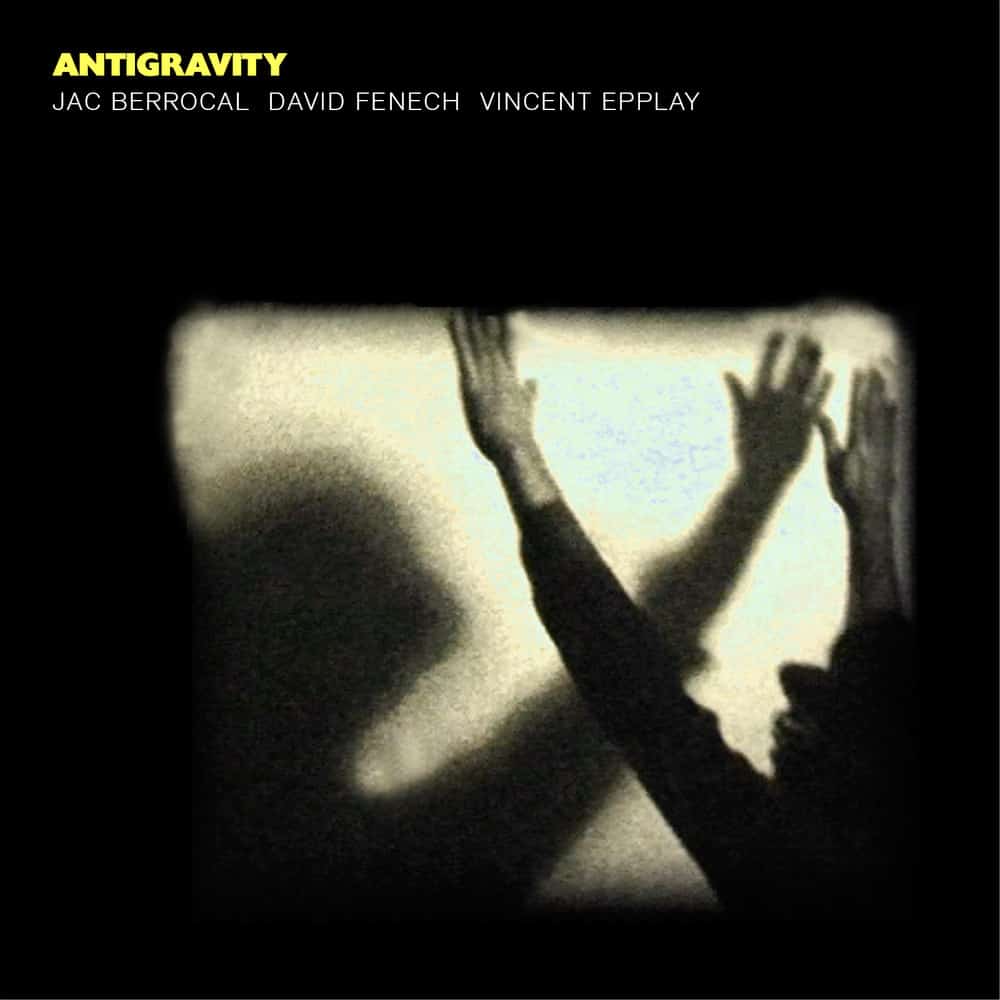

Now Berrocal has found the perfect foil in David Fenech and Vincent Epplay, two fearlessly inventive improvisers, composers and catalysts who create challenging, acutely modernist yet historically aware settings – wrought out of synthesis, guitars, computer processing, field recordings and unorthodox percussions – for Berrocal’s unmistakeable voice and breathtakingly lyrical horn sound to flourish. Fenech cut his teeth in the mail-art scene of the early ‘90s, leading the Peu Importe collective in Grenoble. His 2000 solo debut was recently reissued by Felix Kubin’s Gagarin label, and he has also worked as a software developer at IRCAM, and played with Jad Fair, Tom Cora, Rhys Chatham and James Plotkin; in 2011 he formed a trio with Berrocal and Ghedalia Tazartes for the Superdisque LP. Epplay is a highly regarded sonic and visual artist with a particular interest in aleatory composition and autonomous pieces, concrète, and the puckish reappropriation of vintage sound and film material, with dozens of published works to his name on labels like Planam/Alga Marghen and PPT/Stembogen. He is also responsible for the cover imagery and video work that accompanies Antigravity.

The Berrocal/Fenech/Epplay trio’s first album together, Antigravity is a richly imagined universe combining original compositions and détourned standards. Berrocal revisits his own signature piece ‘Rock N Roll Station’, which first appeared on his ’77 LP Paralleles with chain-wielding, leather-clad wildman of British rock ‘n roll, Vince Taylor, singing the lead, and Berrocal on mic’d up bicycle; here, the Frenchman takes the vocal reins. A barely recognisable interpretation of Talking Heads’ ‘The Overload’ pushes beyond the bush of ghosts into a fourth world dread-zone of stalking drum machine rhythms, humid electronics and jagged guitar phrasing, while ‘Where Flamingos Fly’ reroutes the Gil Evans Orchestra’s classic rendition through the seamiest back-streets of the 13th arrondissement; there, as on the trio’s reading of ‘Kinder Lieder’, the mood is romantic, but stark, isolationist: imagine Chet Baker falling through the glacial sound-world of early PiL or Scott Walker’s Climate of Hunter. Originals include the agitated Iberian psychedelia of ‘Spain’, and ‘Panic In Bali’, which begins in seemingly trad-jazz fashion only to swell into a cacophony of a gurgling electronics and fevered ‘Lonely Woman’ quotations. ‘Solaris’ is a swirling, suspenseful arabesque of whiplash guitars and Black Ark FX, Berrocal’s trumpet hitting deep blue notes while his vocals are sliced and diced and tossed into a yawning void of tape-delay – like Antigravity at large, the result is oblique, dissolving, forever out of reach. Despite the chilly, sometimes austere mood of the album, it is, ultimately, a deeply human and welcoming work, with a playfulness and sly humour pervading: see the anarchic cross-hatch of ‘Ife Layo’, or ‘L’essai des Suintes ou le bal des Futaies’, Berrocal’s poetic disquisition on the infinite variety of female genitalia. Mischief and misdirection are rife here, and fans of Officer!, Henry Cow and the ReR axis will find much to chew on. Play, as we know, is a serious business.

Put another way, and to quote Berrocal entirely out of context, Antigravity is completely crazy, completely timeless, completely out. As its title suggests, the objective is nothing less than lift-off, weightlessness, a total unshackling from earth. Sunglasses on, collar up, let’s go.

LP tracklist :

- A1. Nanook

- A2. The Overload

- A3. Panic In Bali

- A4. Rock ‘n Roll Station

- A5. Where Flamingoes Fly

- B1. Kinder Lieder

- B2. Tsouking Chant

- B3. La Valse des Lilas

- B4. Nanooks

- B5. Solaris

- B6. Ife L’ayo

- B7. Spain

- B8. Riga Centraal

CD / Digital tracklist :

- 01. Nanook

- 02. The Overload

- 03. Panic In Bali

- 04. Rock ‘n Roll Station

- 05. Where Flamingoes Fly

- 06. Kinder Lieder

- 07. Tsouking Chant

- 08. La Valse des Lilas

- 09. Nanooks

- 10. Solaris

- 11. Ife L’ayo

- 12. Spain

- 13. Riga Centraal

- 14. L’essai des suintes ou le bal des futaies

Jac Berrocal – trumpet, voice, plastic microphone, cymbals

David Fenech – electric guitar, bass, voice, electronics, African guitar

Vincent Epplay – synthesizers, drums, metal spring, cymbals, accordion

Anna Byskov – vocals on ‘Le Valse des Lilas’

Recorded in Paris, Montreuil, Riga, Bordeaux, 2011-14

Mastered and cut by Noel Summerville at 3345, London

Photographs and visual edits by Vincent Epplay

Layout by Oliver Smith

Thanks to Villa Arson, Presence Capitale, Capc, Espace d’en Bas, Anna Byskov, Andre Lombardo, Patricia Brignone, Etienne Blanchot, Frederic Mazely, Stephane Broc

LP pressed at Optimal and housed in full colour reverse board sleeve with printed inner bag and download code (MP3/FLAC). CD housed in reverse board digipak.

videos by Vincent Epplay :

reviews :

Some say jazz went wrong when it left the dancehall. But it also lost something when it moved out of the farmyard. Modern jazz abandoned all the bleats, yelps and squelches that were integral to the music from The Original Dixieland Jazz Band through Muggsy Spanier’s ragtime outfit and into the swing era. The beboppers eyed Carnegie Hall (even if they denied it) and considered “s000-eee!” squeals demeaning to artists. The little instruments of the ARCM and BAG circles reintroduced the veterinary, or at least a certain number of untempered and unclean sounds, but jazz had by then pretty seriously toned down the vaudevillian joy of its classic era. Thank fuck for Jac Berrocal. He throws it all back in. He can still play like Chet Baker, Don Cherry or Miles Davis when he chooses, and proves the point on this set’s version of Gil Evans’s “Where Flamingoes Fly”. He can do the Dark Magus stuff as well, as on the brooding “Solaris”. But the better parallel is with Ornette Coleman’s deceptively untutored brass attack, especially from the era with David Izenzon and Charles Moffett. Berrocal seems to reference “Lonely Woman” on “Panic In Bali”, which starts like a French village band reading a pirate score of “She’ll Be Coming Round The Mountain” and ends in dark garbles of sound that could come from pretty much anywhere. Needless to say, Fenech and Epplay don’t limit themselves to strings and percussion, but use whatever’s to hand, including recordings and unorthodox patches. It’s like The Bonzo Dog Band meeting Scott Walker, with Codona booked for the interval music. “L’Essai Des Suintes Ou Le Bal Des Futaies” is an exercise in pudendal poetry that sets Berrocal at the opposite end of his expressive spectrum from the soberly lyrical “Kinder Lieder”. He does an out there version of Talking Heads’ “The Overload” which is scary-beautiful, and retreads his own bonkers “Rock ‘N’ Roll Station”. It’s all a mess… an absolutely perfect mess.

Brian Morton – The Wire #376, June 2015 (link)

Un peu d’eau au moulin de nos amis chauvins: cette première sortie du trio Jac Berrocal / David Fenech / Vincent Epplay constitue non seulement la deuxième référence de Blackest Ever Black produite par des ressortissants français après l’In Advance Of The Broken Arm de l’ami Tomas More sous pseudo December, mais le débarquement en masse sur l’un des labels les plus chébrans du moment de 3 vétérans parmi les plus engagés et résilients notre fier underground parisien: le légendaire trompettiste Jacques-Antoine-Jean-Evariste Berrocal, pilier éternel de l’underground free jazz français depuis le début des années 70 dont la carrière monumentale mériterait un livre en 3 ou 4 volumes, l’hyperactif David Fenech, collaborateur de Ghédalia Tazartès ou Jad Fair dont le premier album vient de reparaître sur le label Gagarin de Felix Kubin et le passionnant Vincent Epplay, artiste visuel, musicien conceptuel et collectionneur de sons étranges qui vient d’offrir, c’est un hasard total, une magnifique mixtape à notre série de Dronecasts.

Résultat de trois années de recherches, improvisations in situ et performances qu’on serait bien en peine, c’était la moindre des choses à attendre de ces trois là, d’étiqueter voire de simplement situer sur un nuancier de couleurs, Antigravity s’insère pourtant comme un charme dans le catalogue plus-noir-tu-meurs de Kiran Sande. La grande différence d’avec le tout venant dark qui s’y déploie ailleurs, c’est que sa noirceur est pleine de teintes et de densités différentes, pleine de couleurs si l’on ose dire. Entre free electronics, vapeurs de jazz modal et bande-originale de film noir au troisième ou quatrième degré, la musique triturée par le trio avec ses instruments et ses souvenirs refuse nettement l’abscons du tout abstrait mais le triangle qu’elle tente de tracer avec les trois trajectoires infiniment dérivantes et compliquées de ses trois membres ressemblent effectivement à un Triangle des Bermudes.

Relecture ectoplasmique et vibrionnante du sublime “Where Flamingos Fly” dans la version canonique du grand Gil Evans, l’extrait ci-dessous c’est tout sauf un morceau de jazz, évidemment, mais surtout tout sauf un exercice pénible de déconstruction du genre qui peuple les étagères poussiéreuses du jazz contemporain. Plus humblement, c’est de la musique en suspension tout du long, furieusement actuelle et suffisamment aux prises avec le monde pour qu’on ose la qualifier de “pertinente”. On est en tout cas aux anges que l’étiquette Blackest Ever Black lui promette d’être entendue au-delà de la niche un peu étriquée de l’avant-garde et de la musique improvisée.

O.Lamm – The Drone (March 2015 – Link)

Jac Berrocal es una misteriosa entidad que ya lleva una notable cantidad de años haciendo música como trompetista pero, en su más reciente aventura, decidió trabajar en colaboración con dos músicos franceses que han estado sacudiendo el circuito avant-garde. Ellos son David Fenech y Vincent Epplay, quienes bajo esta modalidad de trío lograron ensamblar una colección de canciones que van del misterio a la psicodelia, sin dejar de lado una suculenta oscuridad que irá manipulando su ser de modos sumamente inesperados. “Antigravity” es el nombre del álbum que acaban de publicar con Blackest Ever Black, el cual francamente creo que es una de las más grandes maravillas que han sido publicadas en años recientes, principalmente por la escuela, clase y finura con la que se van desarrollando las canciones. “Where Flamingos Fly” es el más claro ejemplo de ello y, si nunca habían escuchado hablar de estas grandiosas entidades, este es un muy buen pretexto para entrarle a su trabajo.

My Blog Cliché (March 2015 – Link)

‘Antigravity’ is a sui generis invocation of the rarest, compelling order coaxed from the French avant-garde by Blackest Ever Black. Around the locus of cult trumpeter Jac Berrocal – who famously appeared in the NWW list and collaborated with Steven Stapleton – David Fenech and Vincent Epplay unfold a deliciously psychedelic mystery steeped in the esoteric traditions of musique concrète, dub and jazz, and played with a DIY post-punk freedom. Whilst best heard deep in the night with lights low and something burning, ironically enough, it’s gotta be the most colourful release yet on Blackest Ever Black, largely thanks to an enormously rich palette of instrumental timbres and adroit mixing trickery finding the mid-point between the Black Ark and IRCAM. Sometimes we see the most vivid colours with our eyes shut and that’s how ‘Antigravity’ feels; a surreal waking dream where we wander the deliquescent, deserted film sets of abandoned Lynch, Buñuel or Jodorowsky’s; zig-zagging in viscous, plasmic time from the bombed-out 4th world of ‘Nanook’ to the humid, playful scene of ‘Panic In Bali’ and the lysergic flashback of ‘Rock ‘n Roll Station’ (a play on his NWW-listed classic), across the modular synth propelled heights of ‘Where Flamingos Fly’ onto dizzy and distorted gamelan imitations of ‘Tsouking Chant’ and the gibber-jawed hallucination of ‘Solaris’. In the final run thru the bush poltergeists of ‘Ife Layo’ we feel the fever sweats dried by ‘Spain”s arid dubs, but we’re no less disoriented and land is still far out of sight. Please don’t wake us up.

Boomkat (April 2015 – Link)

Jac Berrocal appears on the Nurse With Wound list that famously accompanied that band’s debut album, Chance Meeting on a Dissecting Table of a Sewing Machine and an Umbrella, a nearly flawless guide to experimental music. Berrocal’s most famous album, 1976′s Parallèles, is a timeless fusion of free jazz, punk-ish rock and all-round avant-garde zaniness, and it’s good to hear on Antigravity that, nearly 40 years later, he still casts similar magic.

London-formed but Berlin-based label Blackest Ever Black seems a strange place for Berrocal to crop up, even allied as he is here to two younger, less unpredictable musicians. (Although neither guitarist David Fenech nor sound and audiovisual artist Vincent Epplay could be described as predictable.) Blackest Ever Black’s proprietors have built up a reputation as tireless purveyors of doom-laden ambient music, mutant dance and vicious noise, and while each member of this trio has dabbled in the above to certain degrees, Berrocal in particular seems an odd fit. But it takes only a few seconds to deflect any raised eyebrows, as opener “Nanook” (here’s that humor: I can’t confidently say this refers to the classic faux-documentary Nanook of the North, despite the austere sounds and wordless “eskimo” vocals) is dark, moody and more than a little unsettling, with Berrocal’s echoing cornet lines chiming mournfully out of a hazy tapestry of bloated electronics and imprecise percussion. “The Overload” follows without a break, groaning strings and ectoplasmic electronics forming a distinctly dark ambient bedrock for spiky lone horn notes and hissed vocals that owe quite a bit to the famed black metal rasp of singers like Attila Csihar and Alan Dubin, before it breaks out into Genesis P-Orridge circa 1977 territory. Indeed, Throbbing Gristle is a clear influence in the early stages of Antigravity, as a clear mood of disquiet seems ready to settle in for the duration, although the trio linger just on the right side of derivative.

Just as it seems Berrocal, Fenech and Epplay are going to be closer to the traditional Blackest Ever Black aesthetic than I could ever have imagined, and I’m wondering if the former may have been too deferential to his younger colleagues, “Panic in Bali” upsets the tables completely, its curtain-of-rain sample making way for marching band drums and a lead cornet line that is positively celebratory. They then launch into a dub-laden rendition of Berrocal’s older “Rock’n’Roll Station,” including a warped tribute to failed British Elvis-plagiarist-turned-French-rock-star Vince Taylor.

Antigravity is defined by these bizarre, often jarring contradictions. “Where Flamingos Fly,” for example, which follows “Rock’n’Roll Station,” is an elegant, moving, nocturnal jazz instrumental where Berrocal really shines on cornet with an exulting extended solo over searing Fripp-esque guitar lines and torch-song electric piano. “Kinder Lieder” is just as romantic and nocturnal as “Where Flamingos Fly,” pitched somewhere between Bohren and der Club of Gore and the jazzier parts of the Blade Runner soundtrack.

As the album reaches its midway point with the jovial, North African-inspired jazz of “Tsouking Chant (Kinsu)” — there is of course, no chanting — it’s clear these tonal changes are very much the aim, and one can almost picture Berrocal, Fenech and Epplay recording every track with a hint of a mischievous grin. “Nanook” is reprised with even more industrial clang as “Nanooks,” while “La Valse des Lilas” feels oddly symmetrical to “Where Flamingos Fly.” The trio doesn’t allow the listener any time to find his or her bearings; each track emerges from the debris of its predecessor and so overflows with infinitesimal details that to dismiss them as cheeky vignettes would be mere folly. “Solaris” again features wordless chants and searing cornet, but the electronics are more esoteric, even futuristic, while Fenech’s insistent guitar motifs add percussive force. As the vocals build, drenched in reverb and chorus effects, it’s like the Can of Soon over Babaluma had been recorded with Damo Suzuki still on the mic.

It’s to the immense credit of all three artists involved that Antigravity, for all its variety, never escapes their grasp, coming across instead as unbelievably coherent. (Jac Berrocal’s irrepressibly high-pitched cornet surely plays a part in this continuity, for it punctuates every track and comes to define the emotional tone of each one.) Antigravity is a globe-trotting, mind-altering, mysterious and outlandish record all at once, and it’s both emotionally potent and devilishly humourous. So, yes, it does sit incongruously next to its Blackest Ever Black cousins such as Black Rain’s Dark Pool or Exploring Jezebel’s On A Business Trip to London (both excellent, mind), but it just goes to show how diverse the underground scene is today. In the shadows, all are equal, and all are mad, it seems.

Joseph Burnett – Dusted Magazine (April 2015 – Link)

Blackest Ever Black confounding expectations once again with an LP of Jazz and Dub experiments from Jac Berrocal and Co, housed in a stunning full colour/reverse board sleeve with a printed inner bag and download Delirium, colour, excitement and effortless cool give just a snapshot of the range of what is on offer here. Recorded in Paris in 2011 this is one of the most unique listening experiences on wax, as seemingly disparate elements – Jazz, Dub, Musique concrete and a Gallic punk spirit, coalesce into a sound so potent it is a wonder it hasn’t been done before. The range of instruments utilised by the trio in these performances is astounding, not only in the sheer number of instruments (trumpet/cymbals/guitar/synths/accordion…) but in the proficiency and ingenuity with which they are wielded. Guitars yaw and drone in cavernous reverb interjected by sharp trumpet bursts as thickened feedback beds undulate in an alien meter whilst found percussion is effected in real time sounding as though Pierre Schaeffer was being ran through Scientist’s mixing desk. The excellent recording quality and production on this record almost acts as a fourth member to the group, you can’t help but imagine this being recorded in a smoky backstreet in a city of another space and time! For Jac Berrocal, David Fenech and Vincent Epplay this is just another day at the office, but for the unenlightened it is a window into an enigmatic world. Grab this, turn off the lights and breathe in!

Rewind Forward (May 2015 – Link)

Antigravity est le résultat de la conjonction entre trois personnalités (lire notre interview) qui n’ont jamais refréné leurs ardeurs en matière d’exploration des marges. Peu soucieux de se conforter dans l’air du temps ou de convoiter l’efficacité pop, le trio élabore une forme de musique polymorphe, guidée par l’intuition et l’indéterminisme. Synthèse entre post-punk, musique concrète et jazz ectoplasmique, Antigravity pose les jalons d’un non-genre qui fait appel à des résurgences du passé, ou plus exactement des rémanences. Le trio s’immisce à pas de loup dans territoire des ombres: danse de morts-vivants qui célèbre des vies antérieures, jubilé à la mémoire des âmes errantes, élégie funèbre emplie d’une volupté glaciale (dédiée à la mémoire du grand Jacques Thollot, compagnon de route disparu). Et surtout, il ressuscite la trompette ensorcelante de Jac Berrocal, ses murmures chuintés qui font dresser les poils dans la nuque et sa présence magnétique qui s’est faite si rare.

Passé à la postérité avec le cultissime “Rock n Roll Station” enregistré avec Vince Taylor, Jac Berrocal est l’un de ces musiciens de l’ombre dont la carrière est jalonnée de splendeurs délétères, d’excentricités free-punk (notamment au sein de Catalogue, avec les non moins légendaires Pauvros et Artman) et de collaborations sans garde-fous avec des musiciens de tous horizons. Sacré personnage que ce Berrocal, croisement entre Bogart (pour l’élégance impériale), Artaud (pour la poésie possédée) et Alan Vega (pour l’attitude rock’n’roll) qui s’est même fendu de quelques apparitions au cinéma, notamment chez Mocky. Revenu du free-jazz et de la guerilla industrielle (Suicide, Throbbing Gristle et Nurse With Wound sont passés par là), “abonné aux fissures et aux fentes palpitantes”, Berrocal n’a pas jeté les armes et poursuit sa quête chamanique dans un périple ouvert à toutes les latitudes: de Riga (“Riga Centraal”) à Bali (“Panic in Bali”) en survolant la baie d’Hudson (“Nanook”) avec une étape dans les contrées ibériques (“Spain”) ou maghrébines (“Ife l’Ayo”). Dans ce creuset de réminiscences d’un monde miné par les guerres et la crise économique, on distingue ci et là les thèmes résiduels d’un jazz qui n’a plus de jazz que le nom, sussurrements de trompette bouchée qui convoquent les fantômes de Miles Davis, Don Cherry ou Chet Baker. S’entrouvre alors la porte d’un boudoir imaginaire, où le trio traque une poésie tantôt joviale ou lugubre.

En sus de la guitare électrique et des oscillations de synthétiseur modulaire, les maîtres d’oeuvre David Fenech et Vincent Epplay agrippent tout ce qui leur passent par la main, qui un accordéon liquéfié en drone, qui un doudounba ou un senza. Aussi discordants et hétérogènes soient-ils, les élements épars mis en branle par le trio s’agrègent et s’entremêlent avec douceur et limpidité, privilégiant la lame de fond spectrale à la cacophonie free. Les riffs de Fenech se dissolvent dans un essaim de réverb’ tandis que les feulements de Berrocal subissent les assauts d’une giboulée d’infrabasses et d’ondes frémissantes prises en main par le sound artist Vincent Epplay. Folklore imaginaire à la Aksak Maboul (“Tsouking Chant”, “Ife l’Ayo”) ou kinesthésie industrielle (“The Overload”, “Nanooks”), le disque voyage dans les arcanes de la mémoire, jouant avec les effets de déja-vu et de déphasage à l’intérieur d’une forme en elle-même totalement inédite, où les instruments sont malaxés à l’envi dans une glaise électronique. Usant d’effets sonores tout à tour low-fi ou d’une infime précision, le disque fourmille de détails, de textures et de contrastes qui se révélent au fil des écoutes, sans susciter la moindre lassitude.

“Les humeurs s’aiguisent” sur le bonus track (joliment intitulé “L’essai des suintes ou le bal des futaies”, un titre que n’aurait pas renié Julien Gracq) où la prosodie de Berrocal est soutenue par des percussions obsédantes : ici recommence alors le monde, après le déclin de la civilisation. Le temps se suspend et l’ensorcèlement sonore ne prend fin que lorsque s’éteignent les derniers feux, laissant place à une aube froide et bleuâtre. Comme au lendemain d’une corrida sans vainqueur dans une arène dépeuplée, entourée de ruines immémoriales.

Berrocal, Fenech et Epplay ont chacun des pratiques sonores qu’on pourrait qualifier de transversales: le premier, né en 1946, est l’une des figures légendaires de la free music et du post-punk, révéré en Angleterre alors qu’il reste étrangement méconnu en France. Co-fondateur du groupe Catalogue, cet esthète excentrique a fait jaillir ses fulgurances de trompette au gré d’un parcours pour le moins insolite: on l’a entendu aussi bien avec Christophe qu’avec Nurse With Wound , avec Yvette Horner qu’avec Lizzy Mercier-Descloux. Le second, David Fenech, est un électronicien et un guitariste hétéroclite, au style impossible à qualifier: depuis le début des années 2000, il emprunte les voies accidentées de l’improvisation et multiplie les collaborations, en marge du rock et du jazz. Quant à Vincent Epplay, il est à la fois musicien et plasticien, et élabore depuis vingt ans un travail tant visuel que sonore autour de la rémanence et des spectres qui hantent l’inconscient collectif, en usant de synthétiseurs analogiques, de montages d’archives de l’INA et de films tournés en Super 8. A l’occasion de la sortie de l’album Antigravity (lire notre chronique), nous sommes allés à la rencontre de ce trio de franc-tireurs, évoluant sur des sentiers de traverse par delà les genres et les époques. Ce qui a fait dire à un critique anglais que leur collaboration évoquait “du dub mixé par Pierre Schaeffer”.

Comment vous êtes vous retrouvés sur le label anglais Blackest Ever Black ?

DF : On avait listé une dizaine de labels qui nous paraissaient intéressants, on a envoyé des démos et B.E.B. a réagi immédiatement. On a eu d’autres propositions, mais c’est avec eux que le feeling est tout de suite bien passé. C’est un label assez ouvert, et surtout cohérent. Il y a un esprit.

JB : Je ne sais pas trop ce que « cohérent » veut dire. Mais je comprends ce que tu entends par là. Sur le label Futura par exemple, on trouvait une certaine cohérence dans le free. Mais il y avait des nouveaux ingrédients qui arrivaient. Tu avais à la fois du jazz de Nouvelle-Orléans et de la pop complètement d’avant-garde. Mahogany Brain, avec les textes de Michel Bulteau, c’est du punk français avant la lettre ! Et ça n’est pas loin de la poésie sonore non plus. Cohérence, oui, mais pour moi le terme s‘appliquerait davantage à Eddie Barclay par exemple, qui était capable de sortir un disque de poésie de Jacques Doyen avec les structures sonores de Lasry-Baschet d’un côté, et un disque de Vince Taylor de l’autre. Et un slow de l’été dans la foulée, parce qu’il faut bien faire tourner la baraque. Le 45 tours du minet ou de la minette qui se vendait à des millions d’exemplaires, ça lui permettait de payer les orchestrations pour Léo Ferré, qui lui n’allait pas vendre autant. C’est en cela que c’est cohérent.

VE : La cohérence, elle est dans l’incohérence.

DF : C’est d’une « illogique placable », pour reprendre l’expression que j’utilisais pour décrire ma musique.Comment s’est opérée la rencontre entre vous trois ?

DF: Jac et moi, on jouait déjà ensemble depuis cinq ou six ans. On a joué à Nice sur l’invitation de Vincent lors d’une expo à la Villa Arson, et il s’est joint à nous sur scène avec son synthétiseur modulaire; ça s’est fait de manière extrêmement spontanée. On a un autre disque qui sort à la rentrée et qui a été enregistré il y a encore plus longtemps, avec Jason Willett (musicien américain qui a joué notamment avec Half Japanese et The Jaunties, et a fondé le label Megaphone, NDR) et Vincent qui intervient aussi.

VE : On a chacun des pratiques assez distinctes. Je connais la musique de Jac depuis très longtemps. Ca remonte à 1987, alors que j’étais encore étudiant aux Beaux-Arts de Nice. Je faisais déjà de la musique sur cassette et un ami m’avait dit qu’il existait d’autres musiciens qui travaillaient dans cet esprit un peu dadaïste, et il m’avait notamment fait écouter “Rock’n’Roll Station”, le fameux morceau de Jac avec Vince Taylor. Je suis venu habiter à Paris quelques années plus tard et c’est là que j’ai fait la connaissance de Michel Potage, un artiste qui avait laissé tomber la musique pour se consacrer à la peinture et à la poésie. Je l’ai logé quelques jours et il m’a appris qu’il avait travaillé avec Jac – je me suis dit qu’il y avait une sorte de rapport télépathique avec ça. La rencontre s’est opérée par convergence d’esprit, si l’on veut. Vingt ans plus tard, j’ai fait une installation pour l’exposition Le Temps de l’Ecoute à la Villa Arson en 2012 dans laquelle je reprenais tout ce que j’avais filmé et enregistré à l’époque et il se trouve que Jac apparaissait dans l’un de mes films tourné en Super 8. Et comme j’avais l’opportunité d’inviter des musiciens à l’ouverture de l’expo, j’ai invité Jac et David en duo. Et c’est comme ça que notre collaboration a démarré. C’est marrant comment les choses se relient, des années après… Mais ça aurait pu ne jamais se produire. Il a fallu vingt ans d’incubation.

DF : C’est une rencontre. Le mot « rencontre » est important. Je pense qu’on s’est bien rencontré tous les trois.

VE : J’ai toujours fonctionné sur ce mode là, il n’y a jamais eu aucun calcul de ma part. Je ne cherche pas à provoquer les rencontres en tant que telles. Il y a une sorte de magnétisme qui fait que tu rencontres les gens que tu dois rencontrer, c’est un processus naturel. Tout ça pour dire que ça n’a rien d’une collaboration forcée ou d’un featuring opportuniste: ce n’est pas comme pour ces disques ou ces films qui s’allient avec des noms connus, mais de manière totalement artificielle.

DF : Oui, ce n’est pas un hasard si on se retrouve ensemble.Votre connivence artistique semble aller au-delà de la simple collaboration. C’est un disque éminemment contemporain, très atypique dans ses formes et ses textures, mais aussi chargé de réminiscences du passé. Avec un certain sens du collage, de la collision d’univers sonores très hétérogènes – et là je m’adresse en particulier à Jac qui a travaillé avec Steven Stapleton de Nurse With Wound.

JB : Je préfère la notion de collision à celle de collage. Ce sont avant tout des histoires qui s’emboîtent les unes avec les autres, davantage que du cut-up. Je n’ai rien contre le collage, mais c’est très différent de notre manière de procéder.

DF : Parfois, entre Vincent et moi en particulier, on est dans des espèces de battements, de sonorités qui se répondent. J’utilise beaucoup la résonance des cordes de guitare tout en jouant avec la rugosité des riffs, tandis que Vincent utilise beaucoup les sons du Persephone et du EMS qui sont beaucoup plus fluides, or par moments, on a le sentiment d’être dans des harmoniques et des tonalités tellement proches qu’on n’arrive plus à identifier qui a fait quoi. C’est là qu’on se rend compte qu’on est arrivé à créer un tout homogène.

VE : Il y a un gros travail de mixage, en fait. Ce sont des sessions au départ, on laisse les choses se développer sur un terrain commun, mais ce n’est pas de l’impro où chacun resterait sur ses marques. C’est hors codes. David et moi, on fait des propositions de mix sur les sessions, dans le rapport technique au disque. Mais après, il y a une écoute collective et on décide ensemble. Jac, même s’il est moins dans l’aspect technique du maniement de logiciel, contribue aussi en disant ce qu’il faut ajouter ou enlever. Et ça tape juste à chaque fois, on est toujours d’accord là-dessus.

JB : Il n’y a pas quelqu’un qui dit : il faut absolument que je m’entende, les autres je m’en fous. Ca, ça ne peut pas marcher. Alors que c’est ce qu’il se passe dans beaucoup de groupes.

DF : Comme disait Vincent, le mix est extrêmement important. Le quatrième instrument, c’est le studio. Hier, quelqu’un a fait une critique de disque que j’ai trouvé très pertinente, il disait que ça sonnait comme du dub mixé par Pierre Schaeffer. C’est une description que j’ai trouvé assez juste. C’est une approche « musique concrète » qui part de la spontanéité du rock.

DF : Quand on sent que ça marche, on le sait.

JB : Oui, on sent ce qu’il faut garder tel quel, mais aussi là où ça nécessite des petites retouches ou des choses à colorer. Je dirais même qu’il y a une cinquième personne dans le groupe, c’est Noel Summerville, l’ingénieur du son anglais qui s’est occupé du mastering. C’est l’équivalent de Bonnard qui arrive à l’ouverture de l’expo et qui rajoute des dernières touches de peinture.

DF : C’est un magicien, il a vraiment fait un boulot extraordinaire.

VE : Il y avait un risque, c’était de partir dans des directions assez différentes. On a pas mal coupé et il y a certaines choses enregistrées live, comme le début par exemple. Il y a aussi beaucoup d’enregistrements en homestudio, entre chez moi et chez David. Il y avait plein de configurations dans un laps de temps assez large, étalées sur deux ans et demi. On est parvenu à créer une forme de cohésion entre tous ces éléments. Le mastering a permis de mettre en relief tout ça, c’est un peu comme l’étalonnage pour un film. Ca va même plus loin que ça, le mixage peut révéler des choses entièrement nouvelles. On voulait conserver des densités sonores différentes, du low-fi à des choses beaucoup plus précises. A l’écoute du disque, ça se tient. Tout est très ciselé.Comment s’est déroulé l’enregistrement ?

DF : On répétait autour d’un multipistes et moi, je laissais l’enregistreur tourner. C’est la meilleure façon de procéder.

JB : Gilbert Artman a toujours dit ça, que ce soit pour Lard Free, Urban Sax ou Catalogue, il préconisait de tout enregistrer. C’est là qu’on capte des moments de grâce.

DF : Une répétition est souvent mieux qu’un concert ! Il se passe quelque chose d’imprévu, un événement, un accident. Ca peut aussi être une question d’état. Le morceau « Nanook » par exemple est décliné en deux version sur l’album : la première est en live, la deuxième (« Nanooks ») a été enregistrée chez Vincent à 2h du matin de manière totalement spontanée.

JB : Et en ayant bu beaucoup d’eau, je crois ! (rires)

DF : Oui, tellement d’eau pétillante que c’est sorti comme un geyser ! Si on avait pas enregistré, on aurait jamais retenu le truc, ça se serait volatilisé à jamais.

JB: Ca fait partie de la magie d’un couple à quatre, à trois, à deux ou même tout seul. On se dit qu’on a fait un truc, mais on est pas sûr que la deuxième ou troisième prise soit mieux que la première. Il y a l’effet de surprise qu’on ne peut pas réitérer.

DF : C’est un peu comme refaire une blague. Tu fais une blague, tout le monde rigole, mais quelqu’un a mal entendu et te demande de la raconter à nouveau. Et là, c’est le bide assuré. Il y a le moment de grâce sur l’instant, et quand tu veux le refaire, tu n’y arrives jamais.

VE : Mais ce n’est pas de la musique improvisée pour autant, du moins pas au sens propre. Ca participe d’autre chose, c’est une musique de l’instant qui renvoie à plein de réminiscences. Jac joue de la trompette par rapport à des standards, des airs, sans qu’on en prenne forcément conscience. Comme quand il reprend « After the Rain » ou « La Valse des Lilas », qui est à l’origine un titre de Miles Davis accompagné par Gil Evans. Je ne l’avais jamais entendu avant que Jac le joue. C’est une mémoire qui est soulevée.Ca participe d’une forme d’invocation.

JB : Oui, on invoque des fantômes. Ils arrivent on ne sait trop comment. Avec David et Ghédalia Tazartès, on avait enregistré un disque il y a quelques années de cela en Belgique où on joue un thème fantastique des années 1930 qui s’est vendu à l’époque à des millions d’exemplaires : J’attendrais, de Rena Ketty, un tube intemporel qui a été repris par Dalida et que tout le monde connaît, toutes générations confondues. C’est comme le Requiem de Mozart, c’est un thème sacré – et comme tous les requiem, c’est d’une beauté épouvantable. Ce n’est pas par manque d’inspiration qu’on fait des reprises, c’est une convocation de l’inconscient collectif. Tout à coup, l’un d’entre nous lance un thème sans même y avoir réfléchi au préalable. Ca arrive peut-être parce que l’un de nous l’a entendu à la radio, on essaye alors de le rejouer ensemble et éventuellement, ça marche. Tu veux dire que le thème s’est imposé sans que ce soit prémédité?

DF : Ce n’est pas une reprise, c’est une amplification. C’est comme quarante miroirs face à face de J’attendrais.

JB : Des miroirs déformants.

VE : C’est une rémanence du passé. The Overload par exemple, c’est inspiré du morceau homonyme des Talking Heads, mais au final, c’est à cent mille lieues. C’est un prétexte pour faire autre chose. Mais c’est quand même énoncé, car l’inspiration part de là. Mais c’est au-delà de la reprise. C’est un malaxage qui crée autre chose. Les personnes qui écoutent le truc, ça leur pose une double question : comment ont-ils fait ce morceau ? Quelle est la base d’origine ? Ce n’est pas souvent énoncé sous cette forme. Là, ça devient presque conceptuel.

DF : Un peu comme chez les Residents.

VE : Oui, sauf que les Residents le font d’une manière plus ironique. Quand ils refont du James Brown ou du Gershwin, c’est une reprise à la sauce Residents.

DF : C’est tellement digéré et régurgité que ça ne ressemble qu’à eux. C’est de la réappropriation. Et c’est un peu ce qu’on essaye de faire.

VE : Sauf qu’on est encore plus nébuleux.

JB : Ce qu’on fait est plus spectral, disons. On convoque des spectres. On est dans une buée où il y a Eddie Barclay, Catherine Sauvage, Miles Davis avec Gil Evans… C’est un vague souvenir qu’on joue à notre manière vague aussi, car on a pas très bien le souvenir des notes! (rires) On en prolonge l’intention originelle, même si la forme s’en éloigne.Tu as toujours travaillé de cette manière, Jac, en convoquant les réminiscences d’un passé mythique.

JB : Oui, il y a des choses qui reviennent souvent comme Lonely Woman de Ornette Coleman. Je l’ai joué avec des formations très différentes. Je l’ai entendu la première fois sur Europe 1 à deux heures de l’après-midi, alors que j’avais même pas quinze ans. J’arrivais de servir la messe chez les Carmélites, de chez les Franciscaines où j’étais tombé amoureux d’une religieuse – j’avais redoublé ma communion, mais j’aurais bien aimé la doubler , la tripler ou la quadrupler ! En même temps, j’entends Gene Vincent et Vince Taylor à la radio, suivi d’Ornette Coleman et Don Cherry en prime time, c’est un choc énorme ! Je sortais des chants de la Renaissance que j’ai énormément aimé – cette période de 1470 à 1580, jusqu’à Palestrina, une époque magique où on donnait des messes et des concerts en latin. Après les concerts ou les messes, on avait les mamans qui arrivaient avec leurs jeunes filles et qui offraient des gâteaux, ça motive pour faire de la scène !

Tu as un rapport très fort à la liturgie.

JB : A la liturgie, oui ! Pas à la religion. Je ne crois pas en Dieu, mais par contre j’ai un faible pour les saintes ! (rires) J’ai Sainte Emilie à cause de mes dents, j’ai Sainte Rita pour les causes désespérées et puis Sainte Thérèse de Lisieux bien sûr, puisque notre mère nous avait mis au couvent de Sainte Thérèse, et Dieu sait si elle nous a protégé. Je suis très paradoxal. Il y a des gens que le catholicisme a esquinté, moi pas du tout. Ce que j’aime, c’est la théâtralisation, le rituel, les grandes orgues qui ricochent sur les vieilles pierres des chapelles obscures, les saintes ensanglantées, ce mélange baroque de douleur et de plaisir. Par contre, je n’ai jamais cru une seule seconde en l’existence d’un être suprême, c’est pas mon truc. Mais les saints et les saintes existent. Comme Maximilien Kolbe, un prêtre catholique qui a donné sa vie à Auschwitz à la place d’un père de famille sur le point d’être exécuté.

DF : Il faut savoir que Jacques a débuté la scène comme enfant de chœur chez les Carmélites.

JB : Oui, et je sentais déjà une sensualité ambiante. On était en petit short sous nos aubes, tandis que le curé était vieux et moche, c’était un ectoplasme avec le vin de messe qui arrangeait pas les choses, alors que nous on était jeunes et vigoureux, la nuque rasée, tout propres. Va savoir, peut-être qu’on a fait rêver une cinquantaine de carmélites en une demi-heure ! Elles chantaient des chants grégoriens en latin, alors que chez moi, mon père écoutait Louis Armstrong et Erroll Garner – c’était vachement bien d’être exposé à ces deux types de musique à la fois.Tu es souvent assimilé à un improvisateur, alors que tu es plutôt un mélodiste.

JB : Ah, mais ça tu as complètement raison. Ca fait plaisir à entendre. Je rêverais d’improviser, mais tu te rends compte, des bons improvisateurs il y en a très peu, peut-être trois ou quatre par siècle ! Comme disait LF Céline, « un style, c’est rare… il y en a un, deux ou trois par génération ». Le reste, c’est du bavardage. Moi je me considère pas comme trompettiste, déjà. Et je ne dis pas ça pour faire un effet de style, ni pour me diminuer. Je suis un souffleur de trompette, un amant de la trompette qui adore souffler dedans. Et j’essaye de faire au mieux avec mes compagnons de plaisir et d’aventure. Un trompettiste, c’est un instrumentiste à qui on peut demander de jouer n’importe quoi et qui va te le faire au poil. Or, moi, je ne suis pas comme ça !

Retrouves-tu la démarche de Catalogue au sein de ce nouveau trio ?

JB : Non, Catalogue était beaucoup plus free, plus rentre-dedans. La batterie avait une grosse caisse très proéminente, Jean-François improvisait à la guitare par-dessus tout en tenant le truc. Catalogue, je ne sais pas trop comment ça s’est monté. On était en 1979. Je sortais d’une période très « free music européenne » à laquelle j’étais mêlée. Et quand j’ai rencontré Pauvros, on a monté Catalogue, le groupe (d’après le titre de l’un de mes disques). On a été invité dans un festival de free music mais on avait une approche beaucoup plus rock. On a quand même eu beaucoup de succès. Il faut dire qu’on était dans un état très spécial… C’était du rock très free aussi ! (rires) Il y avait aussi des personnalités comme Potage, qui jouait juste deux accords à la guitare tout en éructant, le cinéaste Patrick Prado qui jouait de l’harmonium d’église, Jean-Pierre Arnoux qui jouait sur une batterie d’enfant… C’était incroyable ! On était habillé aussi comme c’est pas permis : des ceintures rouges, des pantalons qui tombent, le nombril à l’air, des chaussures à haut talons… On n’était pas vraiment glamour non plus, on était étranges, bizarres, un peu extra-terrestres. Et puis à côté de ça, on avait des copains qui jouaient en pull jacquard et en pataugas avec des grosses chaussettes ! (rires) C’est difficilement descriptible. Il y a même un mec de jazz qui a dit : « Je pense que c’est du free-punk, mais je n’en suis pas sûr » (rires)

Comment as-tu débuté la trompette ?

JB : Je ne suis pas passé par l’apprentissage classique ; j’ai appris à l’oreille, à l’instinct. J’ai découvert la musique vers l’âge de dix ans, à la fois en écoutant la radio, en et en travaillant les chants de la Renaissance quand j’étais enfant de chœur chez les carmélites. Quant à la trompette, j’ai appris à en jouer avec un armurier et un trompettiste de bal qui étaient tous les deux bourrés ! (rires) Voilà, je n’ai aucune excuse ! (rires) Je suis un gosse, un animal, tu comprends. Je travaille comme ça la musique, au fur et à mesure des rencontres avec des gens qui sont comme moi. Il y a un truc d’instinct, par rapport à d’autres musiciens qui sont seulement rivés sur la technique. « T’es en quoi, là ? Ah ben fallait me le dire que t’étais en fa mineur ! « (rires) Et là, effectivement, si t’es pas en fa mineur de bicarbonate de soude majeur, y’a plantade ! (rires) Tu piges tout de suite que ça va pas le faire!

VE : Tout est question de langage.

JB : Ce qui est fabuleux, c’est de travailler avec des gens qui ont le même instinct. On est une famille, on est des animaux qui travaillent en meute. On est que trois, mais on pourrait être cinquante ! Si il y en a un sur les trois ou quatre qui est mal à l’aise, il faut divorcer rapidement. Tandis qu’entre nous, c’est un mariage extrêmement réussi.

Julien Becourt, Chronicart (June 2015 – Link)

« Je réécoute Antigravity. C’est chamanique. Ça aurait pu être produit par Brian Eno (je pensais notamment au Jon Hassell). Très grand disque. Mais secret aussi. Le genre de petit trésor qu’on a envie de garder pour soi. »

Christophe Petchanatz – May 2015 (link)

« C’est le plus beau disque écouté depuis longtemps. »

Guy GIrard – June 2015

Normally I would consider it my role to make interviewees feel as comfortable as possible from the beginning of the conversation, but the trio of Jac Berrocal, David Fenech and Vincent Epplay, gathered in a room at Fenech’s place for a Skype conversation, have taken it upon themselves to devise a disarmingly cheerful welcome. Seated to the left, Fenech wears sunglasses and waves a fluffy white teddy bear at me (it belongs to his daughter Anouk), to the right Berrocal, not to be outdone, has opted for sunglasses, a black fedora and broad-collared overcoat, and clutches a baby doll to his chest as he takes a seat. Epplay sits between them, cheerfully puffing on an e-cigarette. Behind them is an array of stringed instruments, a guitar amp, shelves packed tight with vinyl.

It’s an instant reminder that while I’m talking to them about an album of ‘serious’ music, Anti-Gravity – steeped in improv, garlanded with shadows, finding a natural home on Blackest Ever Black – it’s not that heavy either. There’s a plenty of breathing space in the mix, ideas skip by, never once over-elaborated, while absurdist humour and even a degree of jauntiness cut through. Originals are interspersed with re-appropriations of jazzy themes spun from Berrocal’s vocabulary as a trumpet player – Gil Evans, Michel Legrand – although ‘The Overload’, while discarding everything else, retains the lyrics and dread mood of the Talking Heads’ song.

Speaking of improv, there’s a lot to be said for the quality of the interplay throughout the interview. This is particularly the case when Berrocal starts spinning what you sense is well-worn tale and before long they’re all – Berrocal included – riffing on, or even gently skewering, the initial theme.

Berrocal is the most seasoned of the three – a crucial figure in the post ’68 French underground, he released a debut album with Roger Ferlet and Dominique Coster, Musiq Musik, in 1973, following travels with Ferlet that had taken him to, amongst other places, Nepal. During the interview, Berrocal describes Tibetan ritual music by mimicking each instrument in a quite extraordinary fashion.

Collaborations since have included Pascal Comelade, James Chance, Jaki Liebezeit, Ghédalia Tazartès and Pierre Bastien, who played double bass on the enduring ‘Rock N Roll Sation’, which famously features spoken word vocals from Vince Taylor and was later covered by Nurse With Wound – and again by Berrocal/Fenech/Epplay on Anti-Gravity.

Fenech and Epplay are hardly slouches though. The former founded an improv collective, Peu Importe, that released two albums in 1996, before releasing his solo debut, Grand Huit, in 2000, and has previously already featured in a trio with Berrocal and Tazartès. Epplay, who is also responsible for the visual aspect of the Anti-Gravity project, including the sleeve and the live visuals, is a well-established sound and visual artist. He takes up the story of the group’s inception.

Vincent Epplay: Jac and David had already been making music together for two or three years, primarily with Ghédalia Tazartès. I’m a visual artist as well and was involved in an exhibition at the Villa Arson in Nice. I was presenting a theatre piece that involved films and recordings, and Jac was a character who appeared in one of the films, a film from 1987. Every artist involved in the exhibition was also asked to make musical selections and invite groups, so for me it was obvious that I should invite Jac and David to play. Very generously, they invited me to play with them on a couple of songs…

David Fenech: We started the concert as a duo and we finished as a trio with Vincent.

Jac Berrocal: It was a triumph!

DF: We fell in love…

VE: The point is it began like that in a rather fortuitous way… and we went on to play a concert together in Berlin very soon afterwards.

DF: So it’s been a about three or four years.

JB: We started doing some stuff in David’s studio, and in Vincent’s studio, to prepare for concerts but we had some recording sessions too, and it became Anti-Gravity.

It makes sense as a title – there’s a lightness of touch, there’s lots of space, it’s quite playful in many ways.

VE: It was recorded over a period of three years in the form of various sessions, we recorded a lot of things and afterwards there was a lot of mixing, some re-recording, voices that were added, it’s not just the raw sound of the sessions, there was a real job of recording, mixing, producing – that was the part that was really me and David but it’s a real collaboration between the three of us.

DF: To come back to the title, I came across the word reading an interview with Moondog, who was saying that there are places in the world where one feels as though one is freeing oneself from gravity’s pull, which have a mystical quality like the Broceliande forest in Brittany for example, where you don’t feel the weight of the earth any more. And I was thinking that that’s what I wanted for our music, to leave behind the weight of everyday life, of gravity, and very pretentiously I thought we could call the record by that name. Because we had a desire to float… if the music can achieve that, that’s great.

JB It’s an attempt!

This point about various places in the world, I wondered about your relationship to world music – you mention various places names, and there are sounds which might be identifiable from different countries, as if it’s a sort of imaginary trip around the world.

JB: Well, David, Vincent and I, although we haven’t necessarily been to the same places we’ve all travelled quite a bit and more or less unconsciously you bring back in your belly, in your head, various sounds and atmospheres that often, quite naturally, we reconstitute in our own way – it can sound oriental, or Japanese, or Chinese or German. Journeys are very important, I started travelling when I was pretty young but I didn’t have tape recorder or a camera, I always said that my camera was my eyes and that my tape recorder was my stomach. So everything I’ve heard in other countries, I hold on to it in my memories, the memory of my intestines, of my belly, of my eyes and my brain. I think it’s the same for David and Vincent. So I would say that very naturally we found ourselves making music that I guess is a kind of world music and it’s a great compliment…

VE: But we never spoke about it…

JB: Yes it was spontaneous, we didn’t really talk about our travels in relation to the music. But there have been journeys to the four corners of the planet – David, among other places, has been to Bali, Syria, Iraq… Vincent has been to Belgium! [LAUGHS]

Jac, before making your first album you’d been on some pretty interesting journeys…

JB: Yes, with my friend Roger Ferlet we went on a big escapade to Pakistan and Nepal, and then Syria, Iraq and Jordan, and at the same time we met people living in terrible poverty, people engaged in struggles, Tibetan culture, Tibet where people are still suffering under the same conditions. In Lebanon I met Palestinians in the camps, in the north of Baghdad we met Kurds who were also living in great poverty, so all that feeds into it. I believe you’re talking about Musiq Musik, that’s music from a journey, music based on travelling. It’s a record that was greatly influenced by the journeys we went on. Especially because we brought back instruments we found along the way, from Syria, Iraq and India.

VE: This was before World music.

JB: It’s the first World music album! [LAUGHS] Everyone else has been trying to catch up!

But it’s not really music in a particular style or idiom, more memories or impressions of a place.

VE: Yes, it’s like reminiscences of certain sounds – but what I didn’t say was that we never set out to try and make an ‘orientalist’ record or anything like that, we’re not really interested in that sort of approach. They are just things which are in each of us, based on separate experiences we’ve had.

DF: If you look at the room behind us you can see a gamelan that was used on ‘Tsouking Chant Kinsu’, but we don’t play gamelan like a Javanese gamelan orchestra would, nothing like it. Jac plays a Tibetan horn. We use the instruments but not in the idiom or the style that they’re used traditionally, it’s really for their sound. And Jac played the kangling, maybe you can explain what that is Jac?

JB: We’re already on to the kangling! Yes the kangling is a Tibetan trumpet of sorts made from a human femur used by the orchestras of monks in the lamaseries during religious ceremonies. We don’t really use it like the Tibetan monks, we use it in our own way. What’s interesting with this type of instrument is that the western instruments have to adapt to it, they’ve got a raw sound, it’s not tuned. Same with the gamelan, the other instrumentation has to find a way to accompany it.

Is that easier anyway when you’re using electronic sounds?

VE: The electronic aspect is a bit my area, I play particular synthesiser, a ribbon synthesizer which is similar which is similar to the ondes Martenot, it’s modelled very much on the earliest synthesizers. It’s not like a modular synth with lots of patches, it’s very simple and intuitive in the way you play it. It’s true that with electronic sounds you’re not necessarily thinking about creating melodies, it’s the textures and things like that you’re after.

JB: But melodies are everywhere, everything’s melodic, even in places where you expect them the least.

DF: Yes, in drum parts…

You’ve talked a bit about this but can you explain how the roles were divided up?

DF: I recorded and played guitar, I sing on a few tracks. Jac is trumpet, voice, human femur, sea shells, noises and sometimes percussion and Vincent is the electronic side, synths, recording when we’re recording at his place, as well as noises and percussion and sounds added afterwards. So we like starting with a recording, that can last 10 or 15 minutes, from which we take the essential, the most interesting part – that’s why the tracks can seem short, because we’ve really reduced them down, like a reduction in the kitchen – but we don’t really have a golden rule. It can be a live recording at two in the morning that’s magical and we say, “Right, we’re keeping that, it’s on the record” – the first track of side two of Anti-Gravity was like that – or it can be lots of layers, one on top of the other, we record more and then we edit until we have the track, and then it can take six months to have the final track – or rather the track is completed over a period of six months.

VE: This way of doing things, you risk losing the coherence, or a narrative thread, but keeping this kind of spontaneity helps, and also we did a lot of sorting through the recordings we’ve made to choose the 13 tracks – a lot of time listening, discussing, to be sure of agreeing on the right selection, to make something that was listenable to from beginning to end.

Were the improvisations very open?

VE: Well there’s one thing that’s very particular to Jac, which is that when he plays the trumpet he’s sometimes playing things, without any prior warning, maybe standards from Coltrane or it could be something like ‘La Valse Des Lilas’ by Michel Legrand, they’re not really things I listen to, it’s repertoire that’s connected to a certain period and a certain style of music, and I think that they’re tunes you have in your instrument, Jac…

DF: And when we play them live, we never play them the same way twice. Our version of ‘Overload’ bears almost no relation to the original, but it’s a starting point.

Do you know the story behind ‘The Overload’, that was it was what Talking Heads thought Joy Division sounded like, without ever having heard them?

DF: No – in that case ours is more like Joy Division!

Speaking of standards, ‘Rock N Roll Station’ is almost a standard in itself now, why did you decide to have it on the album?

JB: Because they forced me – they said, “If we don’t do this, you can’t play with us anymore!”

DF: You could have a whole album just with versions of ‘Rock N Roll Station’!

JB: What’s different with this song is the actual sonic presence of the original Ziggy Stardust… the ghostly presence of Vince Taylor on the track.

There’s a recording of someone talking about Vince Taylor at the end…

VE: It’s Vince, talking about himself in the third person! What I can say is that it’s the first track I heard by Jac Berrocal.

The visual aspect of the project is important to you as well.

VE: I don’t separate out music and images, for me it’s the same thing…

JB: And when we play live we play with Vincent’s films.

VE: But it’s not just the idea of having a film projected behind us, like a kind of support, they’re more like apparitions which function as our stage lighting in a way, they’re more like projections in the sense that they project light. But I work hard to make sure that they’re not images that lead to particular interpretations of the music. It’s a partner, and element, there are elements that appear and disappear, but it’s not too illustrative. It’s more of the order of an amplification, amplifying certain phenomena. Jac is a protagonist, he appears as one of the characters, or a ghostly image.

The ghostly seems to interest you.

DF: It’s a word – “fantome” -that you hear at the end of the record.

Even the sleeve for me is kind of ghostly.

VE: It’s linked to the films too, without us having that in mind initially. But certain of the tracks definitely provoke mental images, cinematic images.

We also hear the words “Ca ne s’explique pas’ (it is inexplicable) on the record. It that linked to music, something in it that can’t be explained?

JB: Partly, certainly with music you shouldn’t over-analyse but I’m using it in a poetic context. I was in Latvia and when I saw Riga Central Station the words came to me almost immediately. It’s a station built in the 40s, decrepit, full of fissures, in a terrible state but which is nevertheless still standing, and which has known a number of turbulent historical moments, and after walking through this station I went straight to the hotel and wrote this brief text called ‘Riga Centraal’. So it was the station that gave me this idea, and then I thought about aurocarias – there aren’t really any in Latvia because it’s not really a warm country – and hotels, old decrepit palaces I’ve visited where nothing works and there are leaks everywhere. When I was in Lebanon I was lucky enough to stay in Jean Marais and Jean Cocteau’s room, at the Palmyra hotel – there was no air conditioning, nothing worked, but Romy Schneider, Agatha Christie and a whole host of people had stayed there. It was an association of ideas, which is not to say that the text is meaningless, it’s just ‘inexplicable’.

Coming back to the sounds on the album, it opens simply with just spring reverb…

DF: Yes, that’s right. It was recorded live during a concert in Bordeaux, so you start the record with a live sound that then it changes very quickly into studio sound. I see it like a character approaching [he makes footstep sounds].

VE: It was also quite a particular concert, commemorating an important festival in France, Sigma, that Jac played at for example, for the avant-garde of the 60s and 70s, and we were invited to play as part of the exhibition telling the story of the festival. It was a place with lots of warehouses, in a space that’s really a cathedral, and this kind of space allows us to record things we wouldn’t be able to capture normally.

DF: And the microphone was at the back of the cathedral, so there’s a lot of reverb.

David and Vincent, that 60s-70s avant-garde, were you aware of it when you were starting out making music?

DF: Well, my neighbour was the boss of a label called Celluloid [founded by Jean Georgakarakos] – Alan Vega, Soft Cell, but also Ghédalia Tazartès, Manu Dibango, Touré Kunda, and I was at school with his son so I already had access to all that without realising it was underground or unknown or anything like that because it was my friend who gave me the records. I discovered Ilitch more recently, Patrick Vian – it was a very fertile scene, you can’t be aware of everything. Let alone in our own era. And obviously I listened to Jac.

VE: For me it was the 80s, I was working with another musician who had an unbelievable record collection and introduced me to things including Jac’s records and all this French scene – Video Adventures, Lard Free, Catalogue (founded by Berrocal) around ‘83. And then I met this friend again, Pascal Bussy, of the Tago Mago label (now Harmonia Mundi), who gave me quite a few cassettes including a famous compilation Paris-Tokyo. It was a small scene but, even without internet, things circulated, people were aware of these things. It was a really small network in France but it reached certain people and, in Paris, for me at least it took on new life in the 90s.

Jac, you don’t really seem to have had any trouble adapting to new eras, through punk and after.

JB: I’ve find myself being invited to participate in all kinds of projects, rock, jazz – and poetry which is important too, so I’ve worked thanks to poets like Jacques Doyen (and other people like Lizzy Mercier-Descloux, with free jazz orchestras, music that was radical at the time, and rock but of the more deviant, punky kind like MKB, Catalogue. It was experimental rock.

DF: Rock-not-rock.

JB: Yes, ‘rock’ doesn’t really mean much in itself, because ‘rock & roll’ is Vince Taylor, Gene Vincent, those people, Elvis obviously. But in rock, as in jazz, there’s a palette which is fairly broad and I was always on that side of people doing free jazz and things like that. Free jazz was a key influence for the post-68 French artists.

JB: I encountered free jazz right at the beginning, thanks to a great radio Europe 1, a commercial radio station, which still exists and which in ‘61 and ‘62 was playing Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry at lunchtime. I’d always liked jazz because my father was a fan of traditional jazz, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and a little bit of bebop, and I fell straight into free jazz and also modern jazz – Charlie Parker, Art Blakey, Miles Davis and then Coltrane, Albert Ayler, Ornette Coleman and all those people. So my influences were free jazz and then rock – it was weird actually because I’d been in a rock band when I was 15 near Paris were we sang in ‘yaourt’ (yoghurt: singing sounds that approximate real words) kind of ‘wenzzanoyeah’. And I should have carried on because for the girls it was interesting…

DF: It was ‘free’ yoghurt!

[At this point Jac makes a joke based on the fact that the word ‘fruit’ in French sounds almost the same as ‘free’…]

JB: Yes I made fruit yoghurt! Which is to say that nobody could speak English but everybody wanted to sing in English. Which was interesting although really it was shameful.

DF: In sound poetry it might wash!

JB: So it’s this mix of music. I also love the music of the renaissance because I started with that when I was 10. To avoid maths lessons, I volunteered for the masses at a Carmelite nunnery and there I heard Gregorian chants in Latin sung by women, which was fantastic. I was lucky enough to hear that music in a church, with a big organ and a choir. I also participated in a polyphonic choir in the 50s, we did concerts and we were invited for important masses – we buried an archbishop in the cathedral of Sens, one of the largest gothic cathedrals in the world. After the mass lots of young girls and their mothers offered us cakes. And it was surprising because we were there, the little singers, next to the coffin, and I immediately saw that we were the stars!

David McKenna, The Quietus (June 2015 – Link)

C’est en 2009, à l’occasion du concert d’ouverture de l’exposition Le Temps De L’Écoute à la Villa Arson que Vincent Epplay a fait appel à David Fenech et Jac Berrocal. Je présentais la pièce Opération Re-recording, un projet élaboré à partir de l’idée de phénoménologie liée à la re-prise de vue et au ré-enregistrement, explique Vincent Epplay. Une sorte d’opération de rembobinage de mes films et d’enregistrements sonores réalisés dans les années 80. Jac Berrocal faisait déjà partie des nombreux personnages fantômes qui apparaissent dans le flux des images et des sons de ce dispositif de projection. Donc, travailler avec lui était l’occasion parfaite pour reprendre la “conversation” ! En guise de conversation, c’est un véritable trio qui se crée ainsi sur la durée, élaborant une matière musicale sans véritable port d’attache, une musique antigravitationnelle, au sens littéral du terme. On a démarré par une série de concerts. Le disque s’est fait sur un temps de maturation assez long, mais tout en gardant un esprit d’expérimentation spontanée — la première prise étant souvent la bonne. Des séances plus appliquées de re-recording pour les voix, les percussions ou les cascades de trompette, se sont faites simultanément, notamment lors de la résidence à la Halle au cuir de la Villette. Le travail de mixage s’est réparti entre David et moi. On a ensuite fait le tri dans les enregistrements et la notion d’antigravité s’est révélée comme la métaphore juste de cette atmosphère étrange qui plane sur l’ensemble du disque. Antigravity Publié sur le très prisé label Blackest Ever Black (Vatican Shadow / Prurient, Ike Yard / Black Rain, Cut Hands), Antigravity fait l’effet d’un tuner sinueux, détraqué, un brin mystique et incantatoire, qui détournerait/ transcenderait des phrases musicales, rock, jazz, folklorique (“Ife Layo”) dans une sorte de nouvelle dimension sonore subliminale. Musicalement débridé, psychédéliquement abstrait, le disque utilise souvent le format reprise (“The Overload” des Talking Heads, “Where Flamingos Fly” de Gil Evans Orchestra ou “Rock’n’Roll Station”… de Jac Berrocal) pour tailler sa pierre philosophale sonore. L’idée de reprise, ou de détournement, est une notion qui occupe le terrain dans pas mal de mes projets musicaux ainsi que dans mes films et certains dispositifs de diffusion, comme les cabines d’écoute, explique Vincent Epplay. C’est une idée que j’ai d’ailleurs tenté de formuler dans une édition livre-K7 à paraître, au titre évocateur, Unholy Copy : reprise sonore, combine visuelle et autres débordements, une sorte de livre-outil à compléter soi-même. Mais sur le disque, cela relève plus souvent de la relecture que de la reprise. C’est d’ailleurs bien plus Jac avec sa trompette qui impulse la chose.

Laurent Catala – MCD Musiques et Cultures Digitales – June 2015 (link)

Surrealist sound-art and serious play from France. Trumpeter Jac Berrocal’s legend rests on his 1976 LP, Paralleles, which included his best-known song, “Rock n Roll Station”, featuring British singer Vince Taylor, who’d achieved fame on the Continent with The Playboys, and later covered by Nurse with Wound. It reappears onAntigravity, in a typically unpredictable, sidereal version, Berrocal now joined by occasional collaborator David Fenech and artist Vincent Epplay. The rest of the album is just as surprising: witness an unbolted cover of Talking Heads’ “The Overload”, Berrocal’s trumpet like Jon Hassell through the looking glass, or the tense, tagliatelle-like guitar / trumpet study, “Solaris”.

Jon Dale – UNCUT August 2015 (link)

At 68, French improv trumpeter Berrocal remains the quintessential Parisian iconoclast and this strange, beautiful LP is the joyous embodiment of his eccentric style, an eclectic mix of folk anarchy, West Coast jazz cool, African kalimba, French poetry and studio dub. All the beauty and terror of jazz at its most lawless.

Andrew Male , MOJO – August 2015 (link)

If you like to feel toasty warm inside knowing that there are still some free-minded jazz musicians out there doing their best to out-avant the avant garde you’ll really go for an album like this one. Bordering on Nurse With Wound concerns, the trio of Jac Berrocal along with David Fenech on guitars and various noisemakers along with Vincent Eppelay on percussion and various other noisemakers waddle between the new jazz and new rock thang with as much ease as a gerbil through a fleshy maze, making for sounds that recall the more outre aspects of 1980 Systematic Records catalog experiments and maybe even that all night college radio show that got axed in a flash. Might not exactly tingle your tastebuds at one sitting, but I do see myself (and maybe you) returning to it frequently like I do all my other Berrocal blockbusters.

Christopher Stigliano – Blog To Comm 2015 (link)

Il est étonnant et en même temps jouissif de voir ces trois noms des musiques free, expérimentales et aventureuses françaises se retrouver sur Blackest Ever Black, mais cela montre bien la diversité des goûts de ce label fort recommandable. Jac Berrocal, du haut de ses soixante dix ans, relève un peu du mythe. Fondateur du projet Catalogue dans les années soixante-dix, mais aussi collaborateur de Nurse With Wound ou Messageros Killers Boys, il a prouvé que sa trompette pouvait s’adapter à toutes sortes d’univers sonores. Avec les bidouilleurs David Fenech et Vincent Epplay, il trouve des partenaires de choix. En effet, son instrument est mis en avant tout du long, avec deux tendances majeures qui s’alternent : un dark jazz à la Bohren & Der Club Of Gore, nocturne et idéal pour des B.O. de films noirs (« Kinder Lieder », « La Valse des Lilas », la très belle reprise du « Where Flamingos fly » de Gil Evans), et des titres plus exotiques, délirants, inspirés autant par les terres inuit, indiennes qu’africaines (« Nanook « Tsouking Chant », « Ife L’ayo », « Panic in Bali »). Le passage d’une facette à l’autre crée un ensemble proche du collage dadaïste, avec tout un travail sur les sons concrets, les motifs de guitare minimalistes ou vagabonds, les boucles électroniques tantôt abstraites tantôt planantes. Mais l’album ne se limite pas à ces domaines. Avec «The Overload », qui reprend le texte d’un morceau mythique de Talking Heads très marqué par Joy Division, c’est à un tout autre groupe que l’on pense : Throbbing Gristle. La boîte à rythmes primitive, quelque part entre « What a Day » et « Hamburger Lady », le traitement de la trompette au delay comme Cosey en avait l’habitude, les bruitages free, tout rappelle ces précurseurs de la musique industrielle. Un autre morceau à part, c’est bien sûr le « Rock n roll Station » que Berrocal avait composé pour l’album Parallèles (1977) avec la voix de Vince Taylor et que Nurse With Wound a réinterprété de nombreuses fois. L’album se divise ainsi, entre hommages, ambiances sombres et romantiques et psychédélisme ethnique déjanté pour finir en spoken word : « L’Essai des Suintes ou le Bal des Futaies ». A écouter comme un trip.

Max Lachaud – Obskure Mag #25

Berrocal / Fenech, le retour ? Yep, et sur un air de western (enfin, d’un western modifié, celui de Nanook, le premier titre de ce CD). Avec le duo, notons que ce n’est plus Tazartès mais Vincent Epplay, artiste sonore de son état et musicien touche-à-tout-ce-qui-sonne (synthés, fied recordings, accordéon, etc). Pas moins de 14 plages, le tout enregistré entre 2011 et 2014. Oui mais alors le tout quoi ? Parce qu’il y en a des choses dans Antigravity… Des improvisations lugubrostères (The Overload), des chansonnettes inspirées par Brian Eno et David Byrne (Panic in Bali) ou Vince Taylor (Rock’n’Roll Station), des reprises (le Where Flamingoes Fly par Gil Evans ou la Valse des lilas, avec Anna Byskov à la voix, qui ferait une belle musique d’ambiance pour parking à agressions), du folk baltringue pour trompette bouchée (Tsouking Chant), des élucubrations expérimentales (Nanooks), une poésie d’exil hôtelier (Riga Centraal) et autres petits trucs parfois un peu fastoches (Solaris). Bref (ah oui, aussi un hommage à Jacques Thollot, et un beau morceau de danse psychotrope : L’essai des suintes ou le bal des futaies)… Bref, disais-je, un catalogue d’excentricités rockobrutales dans un Diapason pour routier chantant (cheers, Soeur Sourire).

Pierre Cecile – Le Son du Grisli (link)

Le CD Antigravity qui existe également en LP voit Berrocal utiliser sa voix, ses trompes tibétaines, trompettes, cloches. Fenech est aux guitares, platines, drums, gamelan, voix. Vincent Epplay drums, percus, synthés, K7, cloches et quelques bizarreries pour moi intraduisibles. Quatorze pièces allant de quelques secondes: a cinq minutes enregistrées a la Villette, à Riga et d’autres endxoits inconnus. Rue du Jura ? Les moments forts sont “Panic In Bali”, Don Aylerien à souhait, “Rock N Roll Station” où Jac joue le role de Vince Taylor. “Where flamingoes fly” de Gil Evans, où Jac se montre plus lunaire que jamais. Le chant enfantin “Kinder Lieder” dans la meme veine, ‘Tsouking chant” swinguant et percussif. Egalement “La valse des Lilas” d’Eddie Barclay et Michel Legrand. Ecouter “Solaris” est un plaisir rare, c’est d’une beauté prodigieuse où se mêlent trompette, voix, guitare électrique, synthés. Calypso “Ife L’ayo”, en hommage à Ornette. Et puis RIga Centraal”, enregistré à l’hotel après la fascination de ce monument grouillant de monde. “Ca ne s’explique pas. J’aime le soir flotter dans les arocarias”. Le dernier morceau est un hommage à son ami Jacques Thollot qui vient de nous quitter. Monk, Ayler, Ellington n’ont fait que se rejouer encore et encore. Berrocal fait de même, différemment, avec de nouveaux arrangements. Un must !

Serge Perrot – Improjazz 218 – September 2015

On my short list of albums of the year. Such an incredibly unique record! Dubby, film noir jazz with hints of post-punk. An avant garde affair, to be sure, but not out of reach for those with an open mind. Highly recommended.

ODDIST – Bandcamp (link)

Unclassifiable, dub-heavy experimentalism from three stalwarts of the French avant-garde. Arch trumpet mangler Jac Berrocal is on scintillating form, leading the trio into uncharted oceans where free jazz, post-punk and electronica form a potent melange, and the fact that “Antigravity” never once lapses into crude self-indulgence speaks volumes for the integrity of its creators. Masterful.

Niccolo Brown – Bandcamp (link)

Synthèse entre post-punk, musique concrète et jazz ectoplasmique, Antigravity pose les jalons d’un non-genre qui fait appel à des résurgences du passé, ou plus exactement des rémanences. Un trio hantologique qui remet le légendaire trompettiste Jac Berrocal au devant de la scène et nous plonge dans un univers sonore d’une richesse inouïe.

Chronicart – TOP 10 2015 (link)

Hin le Berrocal ! Condensé de titres expérimentaux, jazz et d’improvisations, Antigravity, par ses réinterprétations de divers titres (« Where Flamingos Fly », « La Valse Des Lilas »), ses voyages dans des contrées exotiques (« Panic In Bali », « Ife l’Ayo »), se montre extrêmement actuel et est sans aucun doute le disque le plus passionnant de 2015. Jac Berrocal a justement qualifié ce trio de « mariage extrêmement réussi ». Difficile de le contredire.

BugginWebzine – TOP 10 2015 (link)

beaucoup marqué mon année 2015 sans en faire des tonnes pour valoriser leur concept. Zéro démonstration, zéro hystérie. Antigravity présente un cold-jazz très innovant, aux nuances multiples, sans qu’on y perçoive la moindre prétention – on pourrait même qualifier l’album de pudique, un comble pour un disque aussi composite et original.

Julien Lafond Laumond – TOP 2015 – Playlist Society (link)

Der 74-jährige Franzose Jac Berrocal ist schon länger im Geschäft. Von den 1960er-Jahren herauf steht der Freistiltrompeter und Soundpoet für eine dunkle, abenteuerlustige Musik zwischen primitiver Repetition im Zeichen des Rock ’n’ Roll und Noir-Soundtracks. Mit seinem Trio spielte er 2015 etwa das fantastische Album Antigravity ein. Dieses setzt dort an, wo David Byrne und Brian Eno einst mit My Life in the Bush of Ghosts aufhörten

Der Standard – September 2021 (link)